Churches Doing Sermon Series on R-rated ‘Oppenheimer’ Film

Summertime is ‘Church at the movies’ time for many seeker-sensitive and biblically illiterate churches, and the usual blockbuster films are prime pickings: Mission Impossible, Transformers, Super Mario, and even the newest ‘Barbie’ film. These PG and PG-13 films are all ripe for industrious pastors to pluck ‘life lessons’ out of and to uncover the ‘spiritual truths’ out of Bowser singing ‘Peaches’ or Optimus Prime ‘transforming’ into a new creation.

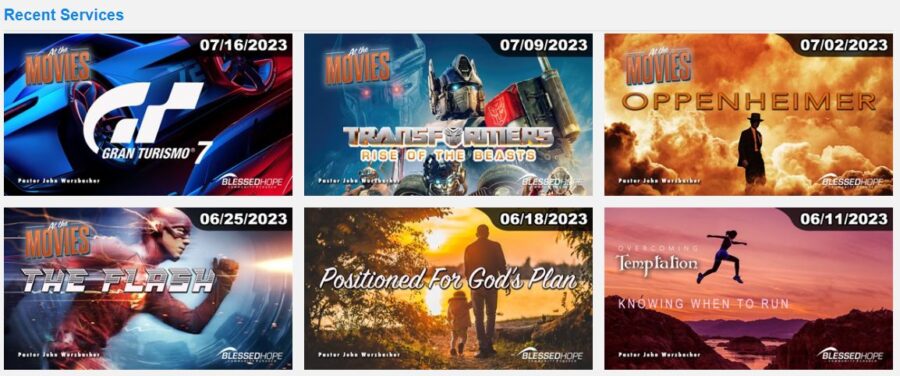

One church has upped the ante, however. Blessed Hope Community Church is a contemporary, non-denominational Christian church in Webster, NY. They make a point of saying they meet Sunday morning in a movie theater with comfy reclining chairs and advertise that if you attend their church, you’ll experience “authentic caring people, exciting, upbeat music, messages that are relevant to your life, and even movie clips on the big screen!”

Led by John R. Wurzbacher, they’ve done sermons on The Flash, Transformers, Gran Turismo, and the R-rated Oppenheimer, which, according to reviewing sites, has “several sex scenes with partial nudity, including long sequences with bare breasts.”

They’re not the first time to do a sermon series on R-rated films and Tv shows. Perry Noble and his new megachurch ‘SecondChance Church’ did one on Game of Thrones a few years back.

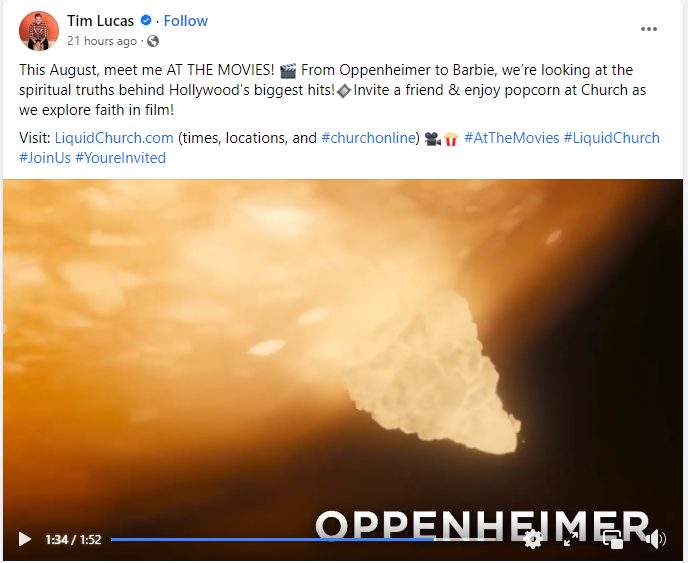

They also won’t be the last to do one on Oppenheimer, as Liquid Church is likewise planning to preach on it in August, where they’ll explore ‘faith in film’

For the church service, Wurzbacher has his congregants watch the trailer for the film and then asks them whether or not they experienced regret, relating Oppenheimer’s regret at building the atomic bomb to people’s regrets at saying unkind words or eating food that gave them food poisoning. Curiously, when he preached this sermon, the film didn’t even come out yet, and he cautions them, “Now I’m not suggesting that you necessarily go watch this film, especially for the fact that it’s rated R.’

Then why not just preach from your bible?

Start now earning cash every month online from home. Getting paid more than ****k by doing an easy job online. I have made **** in last 4 weeks from this job. Easy to join and earning from this are just awesome. Join this right now by follow instructions

.

.

here,═══☛☛ https://victoriaalexis5.blogspot.com/

Make money online from home extra cash more than 18000 to 21000 Dollars. Start getting paid every month Thousands Dollars online. I have received 26000 Dollars in this month by just working online from home in my part time. every person easily do this job by.

.

.

HERE______ lizayharexjohn.blogspot.com/

Start now earning cash every month online from home. Getting paid more than ****k by doing an easy job online. I have made **** in last 4 weeks from this job. Easy to join and earning from this are just awesome. Join this right now by follow instructions

.

.

here,═══☛☛ https://julizaah9.blogspot.com/

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease . . . . observing a spear of summer grass.

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes . . . . the shelves are crowded with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself, and know it and like it,

The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not let it.

The atmosphere is not a perfume . . . . it has no taste of the distillation . . . . it is

odorless,

It is for my mouth forever . . . . I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

The smoke of my own breath,

Echos, ripples, and buzzed whispers . . . . loveroot, silkthread, crotch and vine,

My respiration and inspiration . . . . the beating of my heart . . . . the passing of blood

and air through my lungs,

The sniff of green leaves and dry leaves, and of the shore and darkcolored sea-

rocks, and of hay in the barn,

The sound of the belched words of my voice . . . . words loosed to the eddies of

the wind,

A few light kisses . . . . a few embraces . . . . a reaching around of arms,

The play of shine and shade on the trees as the supple boughs wag,

The delight alone or in the rush of the streets, or along the fields and hillsides,

The feeling of health . . . . the full-noon trill . . . . the song of me rising from bed

and meeting the sun.

Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?

Have you practiced so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun . . . . there are millions of suns left,

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand . . . . nor look through the

eyes of the dead . . . . nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from yourself.

I have heard what the talkers were talking . . . . the talk of the beginning and the end,

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now;

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.

Urge and urge and urge,

Always the procreant urge of the world.

Out of the dimness opposite equals advance . . . . Always substance and increase,

Always a knit of identity . . . . always distinction . . . . always a breed of life.

To elaborate is no avail . . . . Learned and unlearned feel that it is so.

Sure as the most certain sure . . . . plumb in the uprights, well entretied, braced in

the beams,

Stout as a horse, affectionate, haughty, electrical,

I and this mystery here we stand.

For the love of God 😬

Clear and sweet is my soul . . . . and clear and sweet is all that is not my soul.

Lack one lacks both . . . . and the unseen is proved by the seen,

Till that becomes unseen and receives proof in its turn.

Showing the best and dividing it from the worst, age vexes age,

Knowing the perfect fitness and equanimity of things, while they discuss I am silent,

and go bathe and admire myself.

Welcome is every organ and attribute of me, and of any man hearty and clean,

Not an inch nor a particle of an inch is vile, and none shall be less familiar than the rest.

I am satisfied . . . . I see, dance, laugh, sing;

As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side all night and close on the

peep of the day,

And leaves for me baskets covered with white towels bulging the house with their

plenty,

Shall I postpone my acceptation and realization and scream at my eyes,

That they turn from gazing after and down the road,

And forthwith cipher and show me to a cent,

Exactly the contents of one, and exactly the contents of two, and which is ahead?

Trippers and askers surround me,

People I meet . . . . . the effect upon me of my early life . . . . of the ward and city I

live in . . . . of the nation,

The latest news . . . . discoveries, inventions, societies . . . . authors old and new,

My dinner, dress, associates, looks, business, compliments, dues,

The real or fancied indifference of some man or woman I love,

The sickness of one of my folks—or of myself . . . . or ill-doing . . . . or loss or lack

of money . . . . or depressions or exaltations,

They come to me days and nights and go from me again,

But they are not the Me myself.

Apart from the pulling and hauling stands what I am,

Stands amused, complacent, compassionating, idle, unitary,

Looks down, is erect, bends an arm on an impalpable certain rest,

Looks with its sidecurved head curious what will come next,

Both in and out of the game, and watching and wondering at it.

Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through fog with linguists and

contenders,

I have no mockings or arguments . . . . I witness and wait.

I believe in you my soul . . . . the other I am must not abase itself to you,

And you must not be abased to the other.

Loafe with me on the grass . . . . loose the stop from your throat,

Not words, not music or rhyme I want . . . . not custom or lecture, not even the best,

Only the lull I like, the hum of your valved voice.

I mind how we lay in June, such a transparent summer morning;

You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript

heart,

And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet.

Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and joy and knowledge that pass all

the art and argument of the earth;

And I know that the hand of God is the elderhand of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the eldest brother of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also my brothers . . . . and the women my sisters

and lovers,

And that a kelson of the creation is love;

And limitless are leaves stiff or drooping in the fields,

And brown ants in the little wells beneath them,

And mossy scabs of the wormfence, and heaped stones, and elder and mullen and

pokeweed.

A child said, What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child? . . . . I do not know what it is any more than he.

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven.

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropped,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark,

and say Whose?

Or I guess the grass is itself a child . . . . the produced babe of the vegetation.

Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic,

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the

same.

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

Tenderly will I use you curling grass,

It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men,

It may be if I had known them I would have loved them;

It may be you are from old people and from women, and from offspring taken soon

out of their mothers’ laps,

And here you are the mothers’ laps.

This grass is very dark to be from the white heads of old mothers,

Darker than the colorless beards of old men,

Dark to come from under the faint red roofs of mouths.

O I perceive after all so many uttering tongues!

And I perceive they do not come from the roofs of mouths for nothing.

I wish I could translate the hints about the dead young men and women,

And the hints about old men and mothers, and the offspring taken soon out of their

laps.

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere;

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceased the moment life appeared.

All goes onward and outward . . . . and nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

Has any one supposed it lucky to be born?

I hasten to inform him or her it is just as lucky to die, and I know it.

I pass death with the dying, and birth with the new-washed babe . . . . and am not

contained between my hat and boots,

And peruse manifold objects, no two alike, and every one good,

The earth good, and the stars good, and their adjuncts all good.

I am not an earth nor an adjunct of an earth,

I am the mate and companion of people, all just as immortal and fathomless as

myself;

They do not know how immortal, but I know.

Every kind for itself and its own . . . . for me mine male and female,

For me all that have been boys and that love women,

For me the man that is proud and feels how it stings to be slighted,

For me the sweetheart and the old maid . . . . for me mothers and the mothers of

mothers,

For me lips that have smiled, eyes that have shed tears,

For me children and the begetters of children.

Who need be afraid of the merge?

Undrape . . . . you are not guilty to me, nor stale nor discarded,

I see through the broadcloth and gingham whether or no,

And am around, tenacious, acquisitive, tireless . . . . and can never be shaken away.

The little one sleeps in its cradle,

I lift the gauze and look a long time, and silently brush away flies with my hand.

The youngster and the redfaced girl turn aside up the bushy hill,

I peeringly view them from the top.

The suicide sprawls on the bloody floor of the bedroom,

It is so . . . . I witnessed the corpse . . . . there the pistol had fallen.

The blab of the pave . . . . the tires of carts and sluff of bootsoles and talk of the

promenaders,

The heavy omnibus, the driver with his interrogating thumb, the clank of the shod

horses on the granite floor,

The carnival of sleighs, the clinking and shouted jokes and pelts of snowballs;

The hurrahs for popular favorites . . . . the fury of roused mobs,

The flap of the curtained litter—the sick man inside, borne to the hospital,

The meeting of enemies, the sudden oath, the blows and fall,

The excited crowd—the policeman with his star quickly working his passage to the

centre of the crowd;

The impassive stones that receive and return so many echoes,

The souls moving along . . . . are they invisible while the least atom of the stones is

visible?

What groans of overfed or half-starved who fall on the flags sunstruck or in fits,

What exclamations of women taken suddenly, who hurry home and give birth to

babes,

What living and buried speech is always vibrating here . . . . what howls restrained

by decorum,

Arrests of criminals, slights, adulterous offers made, acceptances, rejections with

convex lips,

I mind them or the resonance of them . . . . I come again and again.

The big doors of the country-barn stand open and ready,

The dried grass of the harvest-time loads the slow-drawn wagon,

The clear light plays on the brown gray and green intertinged,

The armfuls are packed to the sagging mow:

I am there . . . . I help . . . . I came stretched atop of the load,

I felt its soft jolts . . . . one leg reclined on the other,

I jump from the crossbeams, and seize the clover and timothy,

And roll head over heels, and tangle my hair full of wisps.

Alone far in the wilds and mountains I hunt,

Wandering amazed at my own lightness and glee,

In the late afternoon choosing a safe spot to pass the night,

Kindling a fire and broiling the freshkilled game,

Soundly falling asleep on the gathered leaves, my dog and gun by my side.

The Yankee clipper is under her three skysails . . . . she cuts the sparkle and scud,

My eyes settle the land . . . . I bend at her prow or shout joyously from the deck.

The boatmen and clamdiggers arose early and stopped for me,

I tucked my trowser-ends in my boots and went and had a good time,

You should have been with us that day round the chowder-kettle.

I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far-west . . . . the bride was

a red girl,

Her father and his friends sat near by crosslegged and dumbly smoking . . . . they

had moccasins to their feet and large thick blankets hanging from their

shoulders;

On a bank lounged the trapper . . . . he was dressed mostly in skins . . . . his luxuriant

beard and curls protected his neck,

One hand rested on his rifle . . . . the other hand held firmly the wrist of the red girl,

She had long eyelashes . . . . her head was bare . . . . her coarse straight locks

descended upon her voluptuous limbs and reached to her feet.

The runaway slave came to my house and stopped outside,

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsey and weak,

And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him,

And brought water and filled a tub for his sweated body and bruised feet,

And gave him a room that entered from my own, and gave him some coarse clean

clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and passed north,

I had him sit next me at table . . . . my firelock leaned in the corner.

Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore,

Twenty-eight young men, and all so friendly,

Twenty-eight years of womanly life, and all so lonesome.

She owns the fine house by the rise of the bank,

She hides handsome and richly drest aft the blinds of the window.

Which of the young men does she like the best?

Ah the homeliest of them is beautiful to her.

Where are you off to, lady? for I see you,

You splash in the water there, yet stay stock still in your room.

Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth bather,

The rest did not see her, but she saw them and loved them.

The beards of the young men glistened with wet, it ran from their long hair,

Little streams passed all over their bodies.

An unseen hand also passed over their bodies,

It descended tremblingly from their temples and ribs.

The young men float on their backs, their white bellies swell to the sun . . . . they do

not ask who seizes fast to them,

They do not know who puffs and declines with pendant and bending arch,

They do not think whom they souse with spray.

The butcher-boy puts off his killing-clothes, or sharpens his knife at the stall in the

market,

I loiter enjoying his repartee and his shuffle and breakdown.

Blacksmiths with grimed and hairy chests environ the anvil,

Each has his main-sledge . . . . they are all out . . . . there is a great heat in the fire.

From the cinder-strewed threshold I follow their movements,

The lithe sheer of their waists plays even with their massive arms,

Overhand the hammers roll—overhand so slow—overhand so sure,

They do not hasten, each man hits in his place.

The negro holds firmly the reins of his four horses . . . . the block swags underneath

on its tied-over chain,

The negro that drives the huge dray of the stoneyard . . . . steady and tall he stands

poised on one leg on the stringpiece,

His blue shirt exposes his ample neck and breast and loosens over his hipband,

His glance is calm and commanding . . . . he tosses the slouch of his hat away from

his forehead,

The sun falls on his crispy hair and moustache . . . . falls on the black of his polish’d

and perfect limbs.

I behold the picturesque giant and love him . . . . and I do not stop there,

I go with the team also.

In me the caresser of life wherever moving . . . . backward as well as forward slue-

ing,

To niches aside and junior bending.

Oxen that rattle the yoke or halt in the shade, what is that you express in your eyes?

It seems to me more than all the print I have read in my life.

My tread scares the wood-drake and wood-duck on my distant and daylong ramble,

They rise together, they slowly circle around.

. . . . I believe in those winged purposes,

And acknowledge the red yellow and white playing within me,

And consider the green and violet and the tufted crown intentional;

And do not call the tortoise unworthy because she is not something else,

And the mockingbird in the swamp never studied the gamut, yet trills pretty well to

me,

And the look of the bay mare shames silliness out of me.

The wild gander leads his flock through the cool night,

Ya-honk! he says, and sounds it down to me like an invitation;

The pert may suppose it meaningless, but I listen closer,

I find its purpose and place up there toward the November sky.

The sharphoofed moose of the north, the cat on the housesill, the chickadee, the

prairie-dog,

The litter of the grunting sow as they tug at her teats,

The brood of the turkeyhen, and she with her halfspread wings,

I see in them and myself the same old law.

The press of my foot to the earth springs a hundred affections,

They scorn the best I can do to relate them.

I am enamoured of growing outdoors,

Of men that live among cattle or taste of the ocean or woods,

Of the builders and steerers of ships, of the wielders of axes and mauls, of the drivers

of horses,

I can eat and sleep with them week in and week out.

What is commonest and cheapest and nearest and easiest is Me,

Me going in for my chances, spending for vast returns,

Adorning myself to bestow myself on the first that will take me,

Not asking the sky to come down to my goodwill,

Scattering it freely forever.

The pure contralto sings in the organloft,

The carpenter dresses his plank . . . . the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild

ascending lisp,

The married and unmarried children ride home to their thanksgiving dinner,

The pilot seizes the king-pin, he heaves down with a strong arm,

The mate stands braced in the whaleboat, lance and harpoon are ready,

The duck-shooter walks by silent and cautious stretches,

The deacons are ordained with crossed hands at the altar,

The spinning-girl retreats and advances to the hum of the big wheel,

The farmer stops by the bars of a Sunday and looks at the oats and rye,

The lunatic is carried at last to the asylum a confirmed case,

He will never sleep any more as he did in the cot in his mother’s bedroom;

The jour printer with gray head and gaunt jaws works at his case,

He turns his quid of tobacco, his eyes get blurred with the manuscript;

The malformed limbs are tied to the anatomist’s table,

What is removed drops horribly in a pail;

The quadroon girl is sold at the stand . . . . the drunkard nods by the barroom stove,

The machinist rolls up his sleeves . . . . the policeman travels his beat . . . . the gate-

keeper marks who pass,

The young fellow drives the express-wagon . . . . I love him though I do not know

him;

The half-breed straps on his light boots to compete in the race,

The western turkey-shooting draws old and young . . . . some lean on their rifles,

some sit on logs,

Out from the crowd steps the marksman and takes his position and levels his piece;

The groups of newly-come immigrants cover the wharf or levee,

The woollypates hoe in the sugarfield, the overseer views them from his saddle;

The bugle calls in the ballroom, the gentlemen run for their partners, the dancers

bow to each other;

The youth lies awake in the cedar-roofed garret and harks to the musical rain,

The Wolverine sets traps on the creek that helps fill the Huron,

The reformer ascends the platform, he spouts with his mouth and nose,

The company returns from its excursion, the darkey brings up the rear and bears the

well-riddled target,

The squaw wrapt in her yellow-hemmed cloth is offering moccasins and beadbags for

sale,

The connoisseur peers along the exhibition-gallery with halfshut eyes bent sideways,

The deckhands make fast the steamboat, the plank is thrown for the shoregoing

passengers,

The young sister holds out the skein, the elder sister winds it off in a ball and stops

now and then for the knots,

The one-year wife is recovering and happy, a week ago she bore her first child,

The cleanhaired Yankee girl works with her sewing-machine or in the factory or

mill,

The nine months’ gone is in the parturition chamber, her faintness and pains are ad-

vancing;

The pavingman leans on his twohanded rammer—the reporter’s lead flies swiftly

over the notebook—the signpainter is lettering with red and gold,

The canal-boy trots on the towpath—the bookkeeper counts at his desk—the

shoemaker waxes his thread,

The conductor beats time for the band and all the performers follow him,

The child is baptised—the convert is making the first professions,

The regatta is spread on the bay . . . . how the white sails sparkle!

The drover watches his drove, he sings out to them that would stray,

The pedlar sweats with his pack on his back—the purchaser higgles about the odd

cent,

The camera and plate are prepared, the lady must sit for her daguerreotype,

The bride unrumples her white dress, the minutehand of the clock moves slowly,

The opium eater reclines with rigid head and just-opened lips,

The prostitute draggles her shawl, her bonnet bobs on her tipsy and pimpled neck,

The crowd laugh at her blackguard oaths, the men jeer and wink to each other,

(Miserable! I do not laugh at your oaths nor jeer you,)

The President holds a cabinet council, he is surrounded by the great secretaries,

On the piazza walk five friendly matrons with twined arms;

The crew of the fish-smack pack repeated layers of halibut in the hold,

The Missourian crosses the plains toting his wares and his cattle,

The fare-collector goes through the train—he gives notice by the jingling of loose

change,

The floormen are laying the floor—the tinners are tinning the roof—the masons

are calling for mortar,

In single file each shouldering his hod pass onward the laborers;

Seasons pursuing each other the indescribable crowd is gathered . . . . it is the

Fourth of July . . . . what salutes of cannon and small arms!

Seasons pursuing each other the plougher ploughs and the mower mows and the

wintergrain falls in the ground;

Off on the lakes the pikefisher watches and waits by the hole in the frozen surface,

The stumps stand thick round the clearing, the squatter strikes deep with his axe,

The flatboatmen make fast toward dusk near the cottonwood or pekantrees,

The coon-seekers go now through the regions of the Red river, or through those

drained by the Tennessee, or through those of the Arkansas,

The torches shine in the dark that hangs on the Chattahoochee or Altamahaw;

Patriarchs sit at supper with sons and grandsons and great grandsons around them,

In walls of abode, in canvass tents, rest hunters and trappers after their day’s sport.

The city sleeps and the country sleeps,

The living sleep for their time . . . . the dead sleep for their time,

The old husband sleeps by his wife and the young husband sleeps by his wife;

And these one and all tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them,

And such as it is to be of these more or less I am.

I am of old and young, of the foolish as much as the wise,

Regardless of others, ever regardful of others,

Maternal as well as paternal, a child as well as a man,

Stuffed with the stuff that is coarse, and stuffed with the stuff that is fine,

One of the great nation, the nation of many nations—the smallest the same and the

largest the same,

A southerner soon as a northerner, a planter nonchalant and hospitable,

A Yankee bound my own way . . . . ready for trade . . . . my joints the limberest

joints on earth and the sternest joints on earth,

A Kentuckian walking the vale of the Elkhorn in my deerskin leggings,

A boatman over the lakes or bays or along coasts . . . . a Hoosier, a Badger, a

Buckeye,

A Louisianian or Georgian, a poke-easy from sandhills and pines,

At home on Canadian snowshoes or up in the bush, or with fishermen off New-

foundland,

At home in the fleet of iceboats, sailing with the rest and tacking,

At home on the hills of Vermont or in the woods of Maine or the Texan ranch,

Comrade of Californians . . . . comrade of free northwesterners, loving their big

proportions,

Comrade of raftsmen and coalmen—comrade of all who shake hands and welcome

to drink and meat;

A learner with the simplest, a teacher of the thoughtfulest,

A novice beginning experient of myriads of seasons,

Of every hue and trade and rank, of every caste and religion,

Not merely of the New World but of Africa Europe or Asia . . . . a wandering

savage,

A farmer, mechanic, or artist . . . . a gentleman, sailor, lover or quaker,

A prisoner, fancy-man, rowdy, lawyer, physician or priest.

I resist anything better than my own diversity,

And breathe the air and leave plenty after me,

And am not stuck up, and am in my place.

The moth and the fisheggs are in their place,

The suns I see and the suns I cannot see are in their place,

The palpable is in its place and the impalpable is in its place.

These are the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands, they are not original with

me,

If they are not yours as much as mine they are nothing or next to nothing,

If they do not enclose everything they are next to nothing,

If they are not the riddle and the untying of the riddle they are nothing,

If they are not just as close as they are distant they are nothing.

This is the grass that grows wherever the land is and the water is,

This is the common air that bathes the globe.

This is the breath of laws and songs and behaviour,

This is the the tasteless water of souls . . . . this is the true sustenance,

It is for the illiterate . . . . it is for the judges of the supreme court . . . . it is for the

federal capitol and the state capitols,

It is for the admirable communes of literary men and composers and singers and

lecturers and engineers and savans,

It is for the endless races of working people and farmers and seamen.

This is the trill of a thousand clear cornets and scream of the octave flute and strike

of triangles.

I play not a march for victors only . . . . I play great marches for conquered and

slain persons.

Have you heard that it was good to gain the day?

I also say it is good to fall . . . . battles are lost in the same spirit in which they are

won.

I ascend from the moon . . . . I ascend from the night,

And perceive of the ghastly glitter the sunbeams reflected,

And debouch to the steady and central from the offspring great or small.

There is that in me . . . . I do not know what it is . . . . but I know it is in me.

Wrenched and sweaty . . . . calm and cool then my body becomes;

I sleep . . . . I sleep long.

I do not know it . . . . it is without name . . . . it is a word unsaid,

It is not in any dictionary or utterance or symbol.

Something it swings on more than the earth I swing on,

To it the creation is the friend whose embracing awakes me.

Perhaps I might tell more . . . . Outlines! I plead for my brothers and sisters.

Do you see O my brothers and sisters?

It is not chaos or death . . . . it is form and union and plan . . . . it is eternal life . . . .

it is happiness.

The past and present wilt . . . . I have filled them and emptied them,

And proceed to fill my next fold of the future.

Listener up there! Here you . . . . what have you to confide to me?

Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening,

Talk honestly, for no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then . . . . I contradict myself;

I am large . . . . I contain multitudes.

I concentrate toward them that are nigh . . . . I wait on the door-slab.

Who has done his day’s work and will soonest be through with his supper?

Who wishes to walk with me?

Will you speak before I am gone? Will you prove already too late?

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me . . . . he complains of my gab and my

loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed . . . . I too am untranslatable,

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

The last scud of day holds back for me,

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any on the shadowed wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the dusk.

I depart as air . . . . I shake my white locks at the runaway sun,

I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift it in lacy jags.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop some where waiting for you

I did not post any of the above reprobate stupidity.

You’re telling on yourself.

M, everybody reading the posts here knows you did it.

What the sam hill is wrong with you?

As I’ve repeatedly said, if you have a problem with something I posted, that you believe is a wrong interpretation of scripture, then post the darned correction.

How hard is that?

You are, in fact, exactly what you accuse me of being … severely arrogant

And phony …

No truly born again Christian would do what you do here, M.

And that’s not a premise. It’s observable fact.

Our resident troll can’t use it’s own screen name, can’t post or do anything beyond 3rd grade level, never has anything intelligent to say or argue, but by golly it knows how to copy and paste.

Good job little troll. 🙄