The current status of McRaney vs The North American Mission Board — particularly the courts’ willingness to categorize virtually every intra-Baptist dispute as an untouchable “church matter” — represents one of the most serious threats to historic Baptist principles in modern American jurisprudence.

Ironically, a legal doctrine intended to protect churches from government control may instead push Baptist institutions out of meaningful participation in civic life altogether.

And if that happens, Baptists will have helped create the very hierarchical, opaque religious system they have historically rejected.

What the Case Is Actually About

Will McRaney, former Executive Director of the Baptist Convention of Maryland/Delaware, sued the Southern Baptist Convention’s North American Mission Board (NAMB) in 2017 after alleging that NAMB improperly interfered in his employment and later damaged his ministry reputation.

According to court filings and documented evidence:

- NAMB allegedly threatened to withdraw roughly $1 million in cooperative funding unless McRaney was removed.

- After his termination, McRaney claims NAMB officials interfered with speaking opportunities and ministry relationships.

- Evidence includes testimony that speaking invitations were rescinded after communications tied to NAMB leadership.

- McRaney also alleges reputational harm, including a photograph displayed at NAMB headquarters indicating he was not to be trusted. Background of the McRaney v. NA…

NAMB disputes wrongdoing and argues the conflict is fundamentally ecclesiastical — an internal ministry dispute beyond the jurisdiction of civil courts.

Increasingly, courts have agreed. And that is precisely the problem.

The Expanding “Church Matter” Problem

Recent rulings have leaned heavily on the church autonomy doctrine, holding that civil courts must avoid disputes involving religious governance. In principle, Baptists should cheer this. Religious liberty matters. Churches must be free from state control. But what is happening now goes far beyond protecting doctrine or church discipline.

The courts are being asked — and are beginning — to treat any dispute between legally autonomous Baptist organizations as inherently religious and therefore legally untouchable.

If that standard holds, then:

- Tortious interference becomes immune if done by a ministry.

- Defamation becomes non-actionable if spoken inside denominational networks.

- Organizational coercion becomes legally invisible if framed as cooperation.

In effect, Baptist entities gain something approaching civil immunity — not because of theology, but because courts will refuse to examine facts at all. That outcome may feel like institutional protection. In reality, it is institutional exile from civil society.

The Misuse of 1 Corinthians 6: When Religious Liberty Becomes Biblical Revisionism

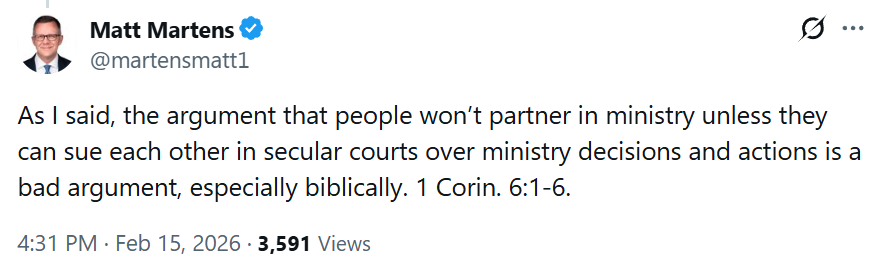

A central public defense of NAMB’s legal position has come from its lead appellate counsel, Matt Martens, who recently argued:

“The argument that people won’t partner in ministry unless they can sue each other in secular courts over ministry decisions and actions is a bad argument, especially biblically. 1 Cor. 6:1–6.”

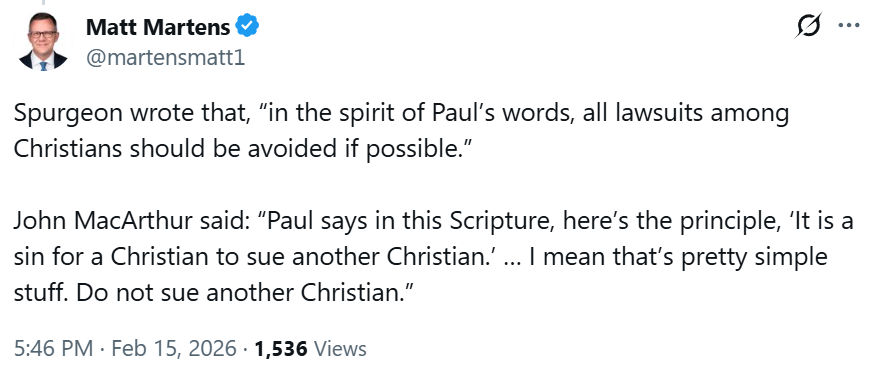

He reinforced the claim by appealing to Charles Spurgeon and John MacArthur, asserting that Scripture teaches Christians must not sue other Christians.

At first glance, this sounds pious. Yet upon closer inspection, it collapses both logically and biblically.

1 Corinthians 6 Is About Church Jurisdiction — Not Civil Immunity

Setting aside for the moment the fact that the very organization Martens is arguing should be biblically immune to suit from other believers has itself taken civil legal action against other believers on numerous occasions, Paul’s rebuke in 1 Corinthians 6 addresses a specific situation: members of the same local church dragging internal disputes before pagan courts rather than submitting to congregational adjudication.

The text itself makes this explicit:

“If any of you has a dispute with another, do you dare take it before the ungodly for judgment instead of before the Lord’s people?” (1 Cor. 6:1)

Paul assumes several conditions:

- The parties are known believers.

- They belong to a shared ecclesial body.

- That body possesses recognized authority to adjudicate disputes.

- The disputants are mutually accountable to that authority.

Remove those conditions and Paul’s instruction loses its operative framework. And that is precisely what Martens’ argument ignores.

The Basic Logical Problem

Martens’ interpretation implicitly claims:

Any dispute between professing Christians is biblically barred from civil court.

But this immediately raises an unavoidable question:

How do we determine who qualifies as “another believer”?

- Do we accept mere self-identification?

- Does conversion mid-lawsuit nullify legal claims?

- Does denominational disagreement invalidate jurisdiction?

- Must one church recognize another church’s discipline?

- Who decides when parties are no longer “brothers”?

Scripture provides an answer — and it is not individual assertion. The New Testament locates Christian identity judicially within the local church.

Church discipline determines who is treated as a brother (Matt. 18; 1 Cor. 5). Paul himself instructs believers to treat the unrepentant as outsiders subject to ordinary social judgment. Without shared ecclesial jurisdiction, the category “brother” becomes legally meaningless.

MacArthur and Spurgeon Don’t Say What Martens Needs Them to Say

Martens cites Spurgeon and John MacArthur as if they support an absolute prohibition. Of course, they do not.

Spurgeon carefully qualified his statement:

“All lawsuits among Christians should be avoided if possible.”

That is pastoral counsel, not a universal legal ban.

MacArthur is even clearer. His commentary explicitly frames Paul’s instruction as applying within the church — meaning disputes among members under shared spiritual authority. That distinction matters enormously.

Paul is not abolishing civil courts. He is rebuking Christians who bypass their own church’s adjudicatory authority. Where no such authority exists, Paul’s instruction cannot apply.

Baptist Polity Makes Martens’ Argument Impossible

Here is the irony: Martens’ reading only works in a hierarchical church. In episcopal or magisterial systems, disputes can be routed upward through binding ecclesiastical courts. Baptists explicitly rejected that model.

There is:

- no Baptist bishop,

- no denominational tribunal,

- no binding inter-church judiciary,

- no mechanism compelling one autonomous Baptist entity to submit to another.

This is not mere polity preference. This is a statement of witness from Baptists to the world around them: God’s law is good, and Baptists stand up for it both inside and outside our churches.

Which means this question becomes unavoidable:

If two autonomous Baptists or Baptist organizations are not part of the same church, where does 1 Corinthians 6 require them to adjudicate disputes?

No such venue exists.

Martens’ interpretation, therefore, produces an absurdity:

- Civil courts are forbidden.

- Ecclesial courts do not exist.

- Accountability disappears entirely.

That is not biblical peacemaking, it is self-serving institutional immunity that threatens the core distinctives of Baptist polity.

Paul’s Command Requires a Church — Not Merely a Brand Identity

The Apostle’s solution was not secrecy but church judgment:

“Is there no one among you wise enough to judge a dispute between believers?” (1 Cor. 6:5)

Paul assumes identifiable elders, recognized authority, and mutual submission. But NAMB and McRaney were not members of the same congregation. They were leaders in separate cooperative entities without shared jurisdiction. Applying 1 Corinthians 6 to that relationship is like applying marriage counseling instructions to two strangers because both wear wedding rings.

The category mistake is fundamental.

The Dangerous Theological Consequence

If Martens’ interpretation were adopted consistently, it would mean:

- Any ministry could avoid civil accountability simply by claiming Christian identity.

- Defamation between ministries becomes non-actionable.

- Economic coercion between religious organizations receives biblical cover.

- Courts must abstain even when no church authority exists to resolve disputes.

In other words, Christianity becomes a legal shield rather than a moral obligation. Paul’s warning against scandal before unbelievers would be turned on its head — creating precisely the public injustice he sought to prevent.

What Paul Was Actually Protecting

Paul’s concern in 1 Corinthians 6 was the witness of the church.

Believers publicly suing one another demonstrated spiritual immaturity because the church itself possessed the wisdom to judge rightly. But when no shared church authority exists, refusing civil adjudication does not protect Christian witness. It destroys it. It signals to the watching world that Christians demand legal privilege without legal accountability, and that we possess superior ability to adjudicate moral/ethical matters that are plainly obvious to believers and unbelievers alike (Romans 2:15). It locates enforcement of the second table of God’s law within the walls of the church, making it hypocritical to continue to insist it should be applied to all people.

The Real Baptist Reading of 1 Corinthians 6

A historically Baptist interpretation looks like this:

- Disputes within a local church belong to the church.

- Disputes between autonomous entities without shared jurisdiction may properly fall under civil law.

- Religious liberty protects doctrine and discipline — not alleged torts unrelated to theology.

Civil courts are not competitors to the church’s authority. They are the mechanism that allows voluntary cooperation to remain genuinely voluntary.

The Irony at the Center of the Case

Martens argues that allowing lawsuits undermines ministry cooperation. The opposite is true. Cooperation without accountability is not cooperation. It is coercion.

And when Scripture is invoked to eliminate accountability rather than encourage reconciliation, biblical authority is not being defended — it is being conscripted.

How Martens’ Theology Became the Court’s Legal Framework

Matt Martens has repeatedly summarized the case with a deceptively simple question:

“The issue is what body gets to resolve whether anyone lied.”

At first glance, this sounds procedural — merely a dispute about jurisdiction. But that framing does far more than describe the case. It defines it. And notably, the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning now mirrors that same conceptual move.

The court did not primarily rule that McRaney’s claims were false, weak, or unsupported. Instead, it concluded that civil courts lack authority even to examine the claims, because doing so would intrude into religious governance and internal ministry decisions.

In other words, the decisive question became not:

- Did interference occur?

- Was reputational harm inflicted?

- Were statements true or false?

But rather:

- Who is allowed to ask those questions at all?

That shift is critical.

As documented in the litigation record, NAMB’s defense — led at the appellate level by Martens — argued that church autonomy turns on the subject matter of the dispute, not the organizational relationship between the parties. Courts, therefore, must abstain whenever resolving a claim would require evaluating decisions connected to religious mission or cooperation, no matter how plainly non-doctrinal the facts are.

The Fifth Circuit adopted precisely this logic, holding that even facially secular tort claims become constitutionally untouchable if adjudication risks examining internal ministry decisions.

The result is a remarkable legal inversion:

Truth becomes irrelevant because jurisdiction disappears.

The court does not determine whether anyone lied — because it concludes no civil body may decide the question at all. This is exactly the outcome Martens’ public argument anticipates.

His theology supplies the interpretive lens through which the legal doctrine operates.

The Quiet Expansion of Church Autonomy

Historically, church autonomy protected churches from state interference in:

- doctrine,

- membership,

- worship,

- and pastoral selection.

But under the reasoning now emerging from McRaney v. NAMB, autonomy expands into something much broader: inter-organizational immunity.

If a dispute arises between religious entities and touches ministry cooperation, courts must abstain entirely — even where claims involve real harms like defamation or tortious interference.

This expansion depends on accepting Martens’ premise that jurisdiction itself is the constitutional injury. Once that premise is granted, every factual dispute becomes secondary. And that is where the argument collides head-on with Baptist history.

“Who Decides?” and the Baptist Confessional Tradition

Martens’ central claim — that the decisive question is who decides whether anyone lied — sounds intuitively Baptist. After all, Baptists fiercely defend church independence. But historic Baptist confessions answer that question very differently.

The Second London Baptist Confession (1689) grounds authority explicitly in the local gathered congregation, not in networks of cooperating ministries.

Likewise, the Baptist Faith and Message affirms:

Each congregation operates under the Lordship of Christ through democratic processes.

Authority is:

- local,

- covenantal,

- and mutually accountable.

It is not transferable through partnerships, funding relationships, or cooperative agreements. Baptists rejected centralized adjudication precisely to prevent institutions from exercising unreviewable authority over one another.

From their earliest associations, Baptists insisted that cooperation creates fellowship, not governance. Associations could advise. Conventions could recommend. Entities could partner.

But none could exercise binding judicial authority over another autonomous body. That distinction is foundational.

Yet Martens’ framework implicitly treats cooperative ministry as jurisdictional authority — meaning disputes arising from cooperation must remain inside a protected religious sphere.

Historically, Baptists denied exactly that claim. If cooperation created jurisdiction, Baptist associations would have functioned as courts. They never did, and they never should.

Why Civil Courts Were Never the Enemy

Contrary to modern assumptions, early Baptists did not reject civil adjudication.

They appealed constantly to civil courts — not to resolve doctrine, but to protect liberty, contracts, and reputation.

Their argument was simple:

- The church governs spiritual matters.

- The magistrate governs civil ones.

- Confusing the two corrupts both.

The emerging McRaney doctrine collapses that distinction by declaring civil harms unreviewable whenever religious actors are involved. That is not Baptist separation of church and state. It is a fusion of ecclesial identity with legal immunity.

The Confessional Problem Martens’ Framework Cannot Solve

Martens claims that he is defending a religious institution’s right to decide whether someone in its employ lied. What he is actually defending is a religious institution’s “right” to determine what a lie is.

Historic Baptist theology answers:

- The local church, when the dispute is ecclesial.

- Civil authority, when the dispute concerns civil injury.

What Baptist theology has never recognized is a third category:

autonomous religious institutions exercising authority without either church jurisdiction or civil accountability.

Yet that is precisely the category the current legal reasoning creates. It leaves disputes neither inside the church nor inside civil society — but suspended in an accountability vacuum.

The Irony Baptists Should Notice

The argument advanced in defense of Baptist autonomy now risks producing a system Baptists historically opposed:

- authority without hierarchy,

- discipline without jurisdiction,

- and immunity without confession.

In attempting to protect ministries from government intrusion, the courts may instead redefine Baptist cooperation as something Baptists themselves never believed it to be. And if that redefinition stands, the question “who decides?” will no longer have a Baptist answer at all. And ironically, many of the same voices who routinely decry the “unaccountability” of the court of public opinion (discernment blogs, YouTubers, etc.) are siding with a legal position that will leave them with no recourse at all, the moment a defamatory online voice claims a similar religious identity.

Baptists Never Believed in Secret Justice

The irony here is profound.

Historic Baptist theology rejects precisely the kind of closed, internal dispute system now being implicitly created.

Baptists were dissenters. They rejected ecclesiastical courts. They opposed state-church privilege. They insisted religious life should exist openly under the same civil law as everyone else.

The Baptist witness has always included:

- transparency,

- voluntary cooperation,

- and accountability under ordinary civil authority.

Unlike episcopal or hierarchical traditions, Baptists have no magisterium, no bishopric, and no ecclesial court of final appeal. When cooperation breaks down between Baptist bodies, there is no internal judicial mechanism capable of delivering binding justice.

Civil courts were never enemies of Baptist life — they were safeguards ensuring voluntary cooperation remained genuinely voluntary. If civil courts now refuse jurisdiction entirely, ministers and churches harmed by other ministries are left with no redress whatsoever.

The Dangerous Logic Emerging in Court

As highlighted in recent analysis by The Baptist Report (“Leaders Warn Foundational Principles at Stake”), the legal arguments advanced in defense of NAMB increasingly rely on portraying Baptist cooperation as functionally hierarchical (the ERLC under NAMB president Kevin Ezell’s ally Russell Moore originally lied to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals that the SBC was hierarchical, only to later blame the obvious and egregious lie on being rushed).

That framing is historically foreign to Baptist polity. Yet it carries enormous legal consequences.

If courts accept that cooperation equals submission to religious governance, then any Baptist organization partnering with another implicitly forfeits access to civil remedies.

This effectively converts voluntary cooperation into a de facto hierarchy — the very structure Baptists rejected for four centuries. Even more troubling, it signals to courts that Baptist institutions prefer internal secrecy over public accountability.

When Religious Liberty Becomes Civic Withdrawal

Here is the deeper issue.

Religious liberty protections exist so churches may participate freely in public life — not withdraw from it.

But if Baptist disputes are categorically barred from civil adjudication, Baptist organizations become legally unique actors:

- able to affect reputations,

- influence employment,

- and exert financial pressure,

while insulated from ordinary legal scrutiny.

Courts will increasingly treat Baptist institutions as private religious enclaves, operating outside normal civic frameworks.

That undermines Baptist witness in two ways:

- Externally, it signals that Baptist ministries prefer immunity over transparency.

- Internally, it incentivizes power consolidation without accountability.

Neither reflects historic Baptist convictions about truth, conscience, or voluntary association.

The Opposite of Baptist Polity

The emerging legal logic produces an outcome Baptists should find alarming: Disputes must be resolved secretly within institutions that lack binding authority to resolve them.

That is not Baptist governance. That is closer to medieval ecclesiology than free-church tradition.

Baptists have historically insisted that religious organizations, precisely because they are voluntary associations, must remain accountable through ordinary civil mechanisms when disputes involve contracts, reputations, or economic harm.

The McRaney case risks replacing that model with one where:

- cooperation creates legal vulnerability,

- accountability disappears,

- and institutional power becomes effectively unchecked.

Why This Matters Beyond One Lawsuit

This is no longer about Will McRaney or Kevin Ezell. It is about whether Baptist life can exist openly within American civil society.

If every inter-ministry dispute is deemed a “church matter,” then Baptist institutions are functionally declaring:

“We do not wish to be governed by neutral principles of law.”

Courts may eventually take that claim seriously — and respond by treating Baptist entities as legally separate from ordinary civic participation. That outcome anabaptizes the Baptist cultural witness.

The Baptist Alternative

Historic Baptist principles point to a better path:

- Churches govern doctrine and membership.

- Civil courts adjudicate torts and contracts using neutral principles.

- Cooperation remains voluntary because accountability exists.

Religious liberty protects belief and ecclesiastical authority — not alleged misconduct unrelated to theology. Allowing courts to hear secular claims does not establish a state church. Rather, it preserves the credibility of religious institutions operating in public life.

The Real Danger Ahead

The greatest danger of the McRaney litigation is not that a ministry might lose a lawsuit. It is that a supposedly Baptist institution may win a legal theory that quietly destroys Baptist ecclesiology.

A system where ministries cannot be held accountable in civil court is not a triumph of religious freedom. It is an abandonment of Baptist convictions about transparency, autonomy, and truth lived openly before the world. And if Baptists continue down this road, they may discover too late that immunity is indistinguishable from irrelevance.

Note: Recently, over 50 Baptist leaders signed an amicus brief asking the Supreme Court to hear McRaney’s case. Much like the above article, it argues that the Fifth Circuit dangerously expanded the church-autonomy doctrine by treating voluntary Baptist cooperation as ecclesiastical authority. Because Baptists lack hierarchical courts, the ruling leaves ministers and Baptist institutions with no forum — religious or civil — to resolve disputes involving defamation or interference. The brief contends the ministerial exception protects only a church’s authority over its own ministers, not third-party religious entities, and urges the Supreme Court to intervene before church autonomy becomes a blanket immunity from ordinary law.

For further reading (including on the related matter of Garner vs the SBC), check out Jon Whitehead’s recent articles here:

https://centerforbaptistleadership.org/no-religious-liberty-doesnt-depend-on-protecting-defamation/